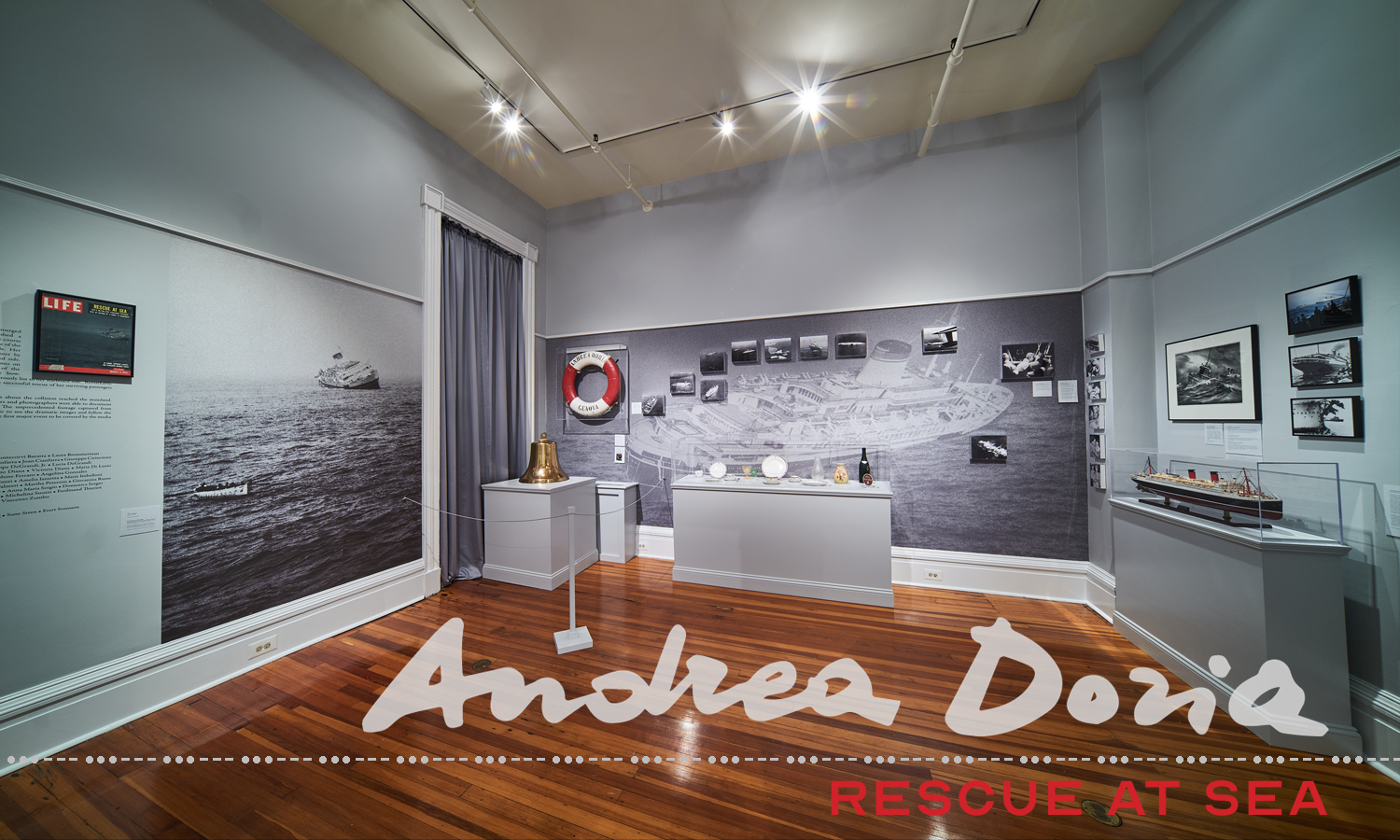

Currently on view in the first floor Print Gallery

Pride of Post-War Italy

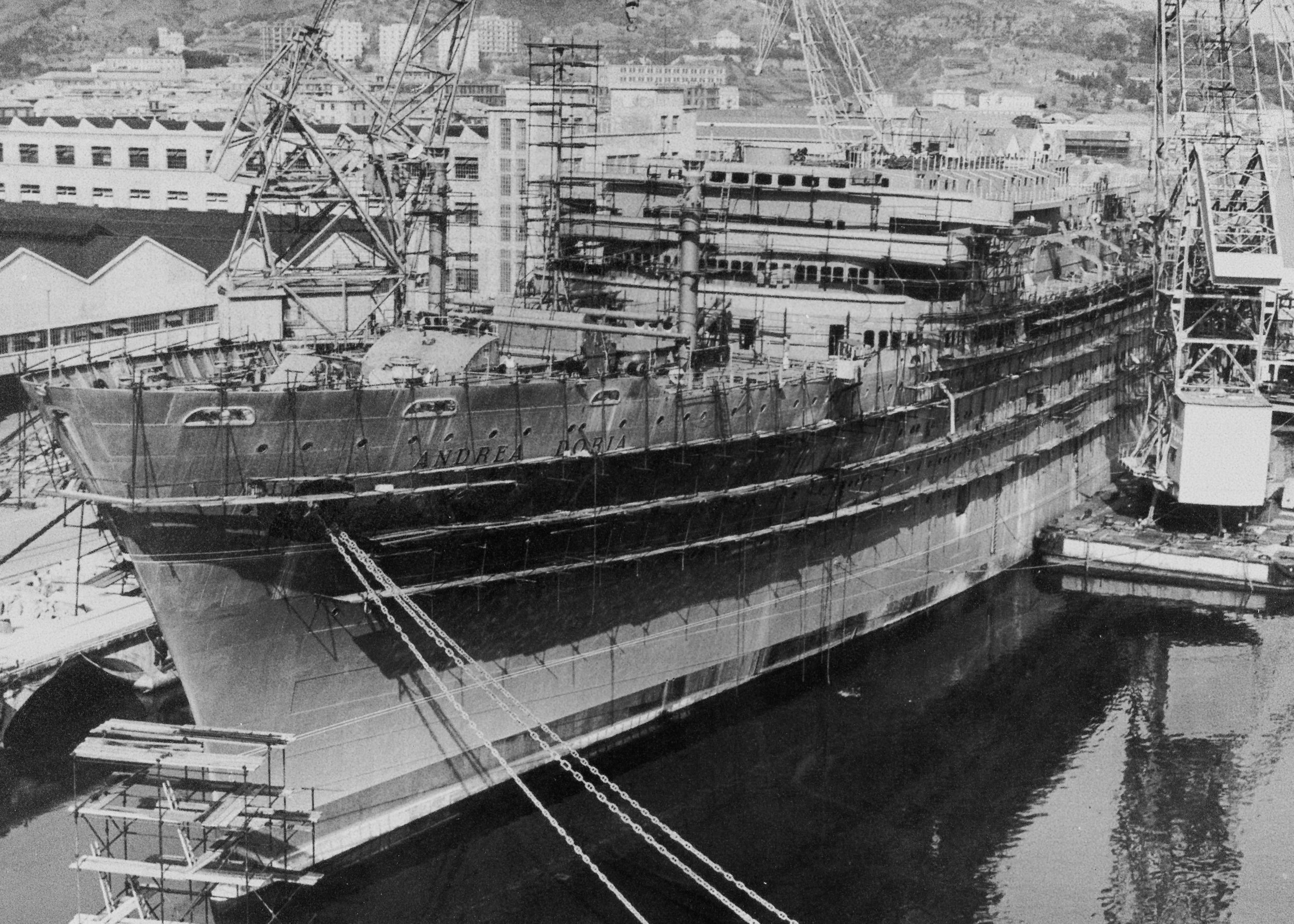

SS Andrea Doria, Reproduction of a photograph, c. 1951, Collection of John Moyer; The SS Andrea Doria was built at the Ansaldo Shipyard in Genoa, Italy at a cost of $29 million and launched on June 16, 1951.

The Italian ocean liner SS Andrea Doria was launched on June 16, 1951, and for a country recently ravaged by war, she became a source of national pride and a symbol of a more prosperous future for Italy. The luxury liner received its name from Italian hero Andrea Doria (1468-1560), an imperial admiral of the Republic of Genoa who fought multiple sea battles against the Ottoman Empire. The Andrea Doria was entered into service two years later on the Genoa to New York line at a time of peak transatlantic ocean liner service, and was well-travelled by vacationers and Italian immigrants alike. By all accounts the Andrea Doria was a beautiful ship; she was a mid-century modern marvel decorated with specially commissioned art earning her the designation of a floating art gallery.

Life aboard the Andrea Doria was a whirl of glamour and sophistication, with well-appointed staterooms, common areas adorned with fine art, and endless entertainment—divided into first class, cabin class, and tourist class. Passengers also included Italian immigrants seeking new opportunities in America, carrying with them all of their worldly possessions.

Just three years after her maiden voyage in 1953, the Andrea Doria set off on her 101st, and ultimately final, journey from Genoa to New York on July 17, 1956. The ship could carry a maximum of 1,800 people, including passengers and crew. On that final voyage, 1,706 people were on board under the command of Captain Piero Calamai, a respected veteran of the sea.

Italian Line promotional booklet, c. 1952-1953, Private collection

July 25, 1956

MS Stockholm, Photograph, 1956

The Nantucket Lightship was reporting dense fog along the Eastern Seaboard on Wednesday, July 25th. The Stockholm was heading east toward Sweden while the Andrea Doria was headed west to New York. There are many factors that contributed to the fatal collision between the two vessels 45 miles off the coast of Nantucket. Both had radar equipment, but only the Stockholm had a reinforced steel bow, capable of breaking through icy waters in the North Atlantic—a feature which would prove disastrous.

At about 10:45 PM the radar on the Andrea Doria noted an approaching vessel at 17 nautical miles away. Captain Piero Calamai and the other officers determined that the other ship was on a parallel route and would soon pass the Andrea Doria on her starboard (right) side with more than one mile between them. Ernst Carstens-Johannsen, the 3rd Officer left in charge of the Stockholm, soon after clocked the Andrea Doria’s location but came to the opposite conclusion. Carstens thought the Andrea Doria was preparing for a port (left) side pass, which was more common, so he ordered a 22-degree shift starboard believing he was expanding the distance between the vessels. The Stockholm and Andrea Doria were set on a collision course.

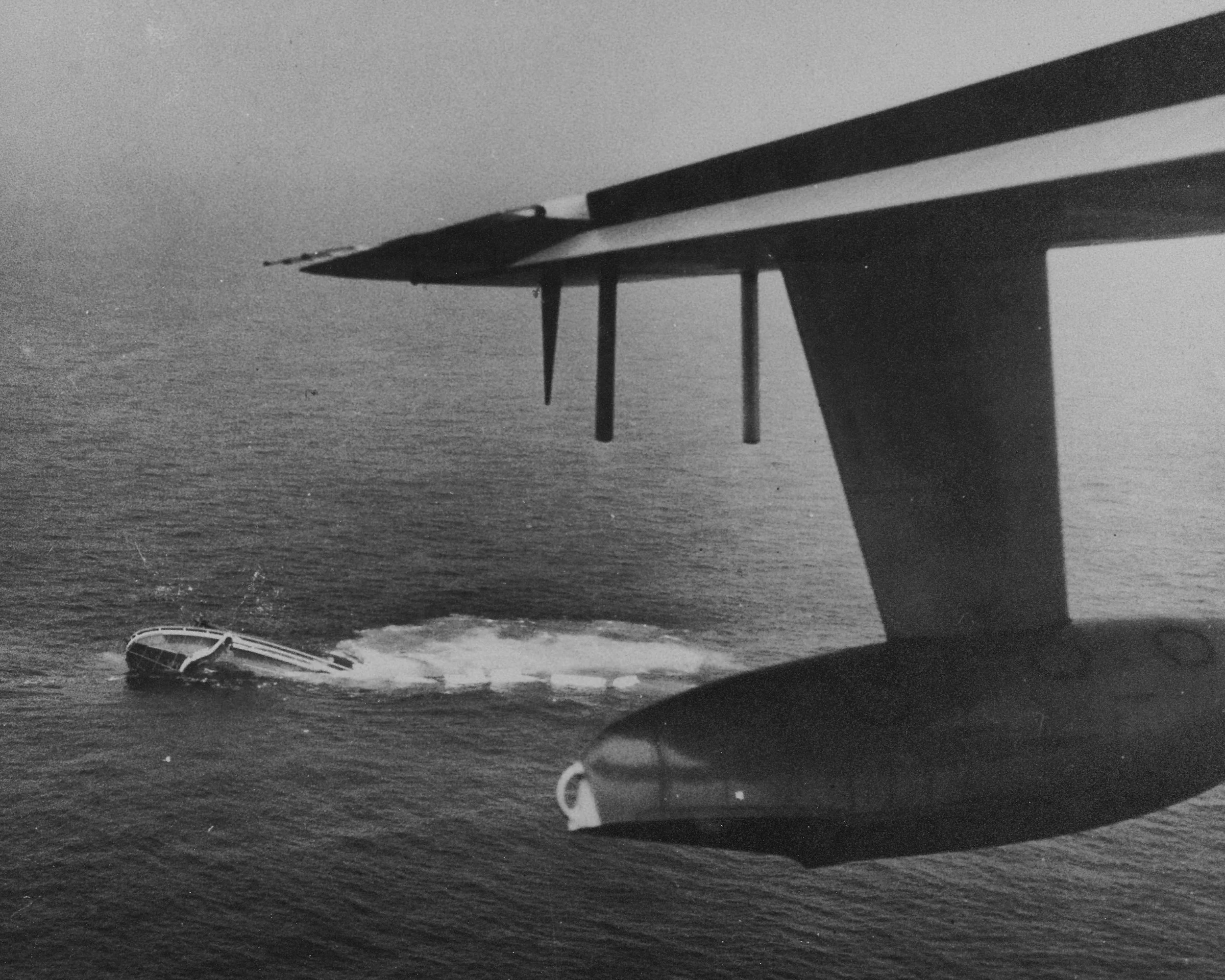

Shortly after 11 PM, the Andrea Doria emerged from the fog and the two vessels established a visual, but it was too late. Despite last-minute course corrections, the Stockholm crashed into the side of the Andrea Doria at a near perfect 90-degree angle. Her steel-enforced bow penetrated the Italian liner by almost forty feet and tore open her starboard side. The impact killed 46 passengers in their cabins on the Andrea Doria and five crew members of the Stockholm who had been working in the bow. Immediately the Andrea Doria began to dangerously list to her starboard side. Remarkably, she stayed afloat for 11 hours, allowing for the successful rescue of her surviving passengers and crew.

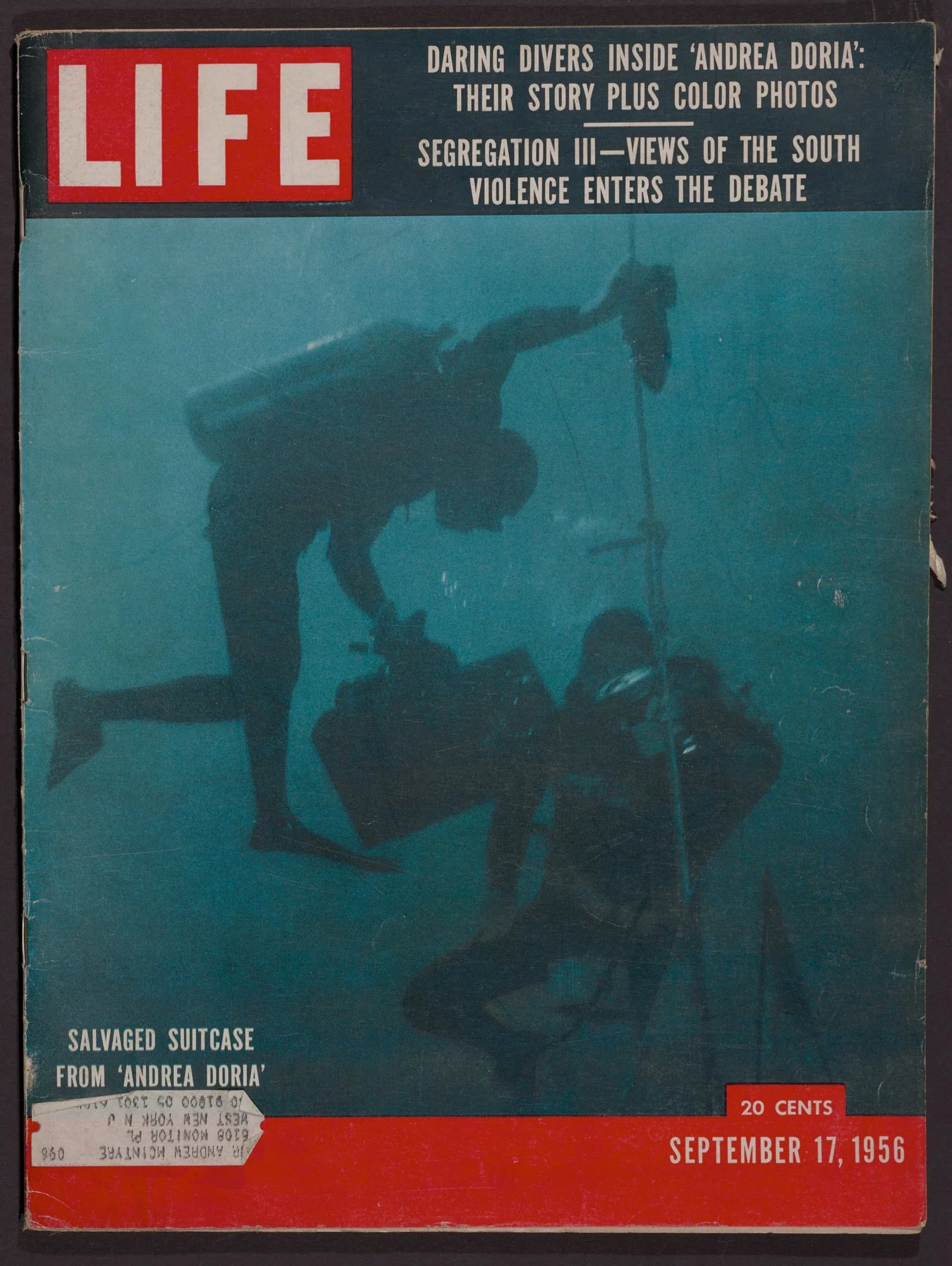

In the early morning hours of July 26th, news about the collision reached the mainland. Due to the wreck’s proximity to shore, reporters and photographers were able to document and film the Andrea Doria’s final moments. The unprecedented footage captured from helicopters and rescue boats enabled the public to see the dramatic images and follow the rescue and sinking from their homes. It was the first major event to be covered by the media in real time.

Paramount News: The Eyes and Ears of the World, “Death of a Ship: Andrea Doria Lost in Collision”, Newsreel, 1956, Courtesy of the Sherman Grinberg Library

This and other newsreels are screened in the museum for the duration of the exhibition.

“Bonsoir...”

The Andrea Doria had enough lifeboats for every person on board, but the circumstances of the crash made half unusable. Captain Calamai quickly sounded the SOS. What followed was the largest peacetime rescue ever made at sea. The nearby freighter Cape Ann arrived first and took on 129 survivors, while the US Navy vessel Pvt. William H. Thomas took 159. After the Stockholm’s crew determined that she was seaworthy, she was able to rescue 545. The ocean liner Ile de France was en route to her homeport when her captain decided to turn the ship around. The French crew rescued 753 survivors from the Andrea Doria, who recall being welcomed on the Ile de France with a gracious “bonsoir.” Captain Calamai intended to go down with his ship, but was persuaded by his officers to disembark and join 76 others aboard the Edward H. Allen, another naval vessel sent to assist. The Andrea Doria ultimately foundered shortly after 10 AM on Thursday, July 26, 1956.

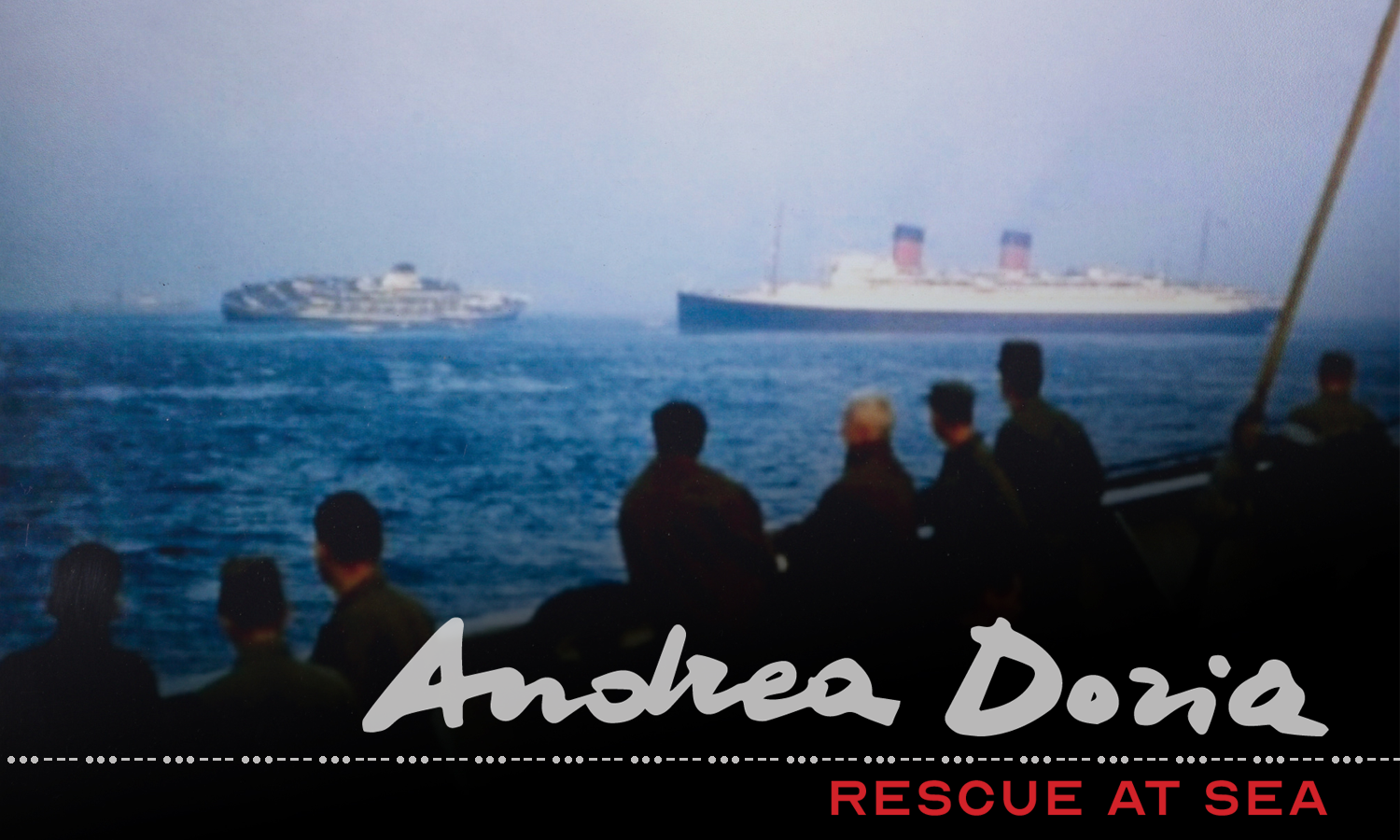

The Ile de France (foreground) and a Navy rescue ship (upper left) rescue passengers from the Andrea Doria, Photograph, 1956, Collection of John Moyer

The Andrea Doria lies on her side 250 feet below the sea, approximately 50 miles south of Nantucket Island. Her location was always known, and underwater photojournalist and filmmaker Peter Gimbel was the first person to scuba dive to the wreck only a day after the sinking. Due to the wreck’s proximity to shore and its relatively shallow depth, which can be reached without a submersible, it has been a siren call to divers for decades. Strong currents, poor visibility, and the disorienting position of the wreck make dives to the Andrea Doria extremely dangerous and the diving community has dubbed it the “Mount Everest of Shipwrecks.” In 1993, diver John Moyer was awarded an Admiralty Arrest in US Federal Court and named Salvor in Possession of the wreck. In the ruling, the judge stated Moyer’s “research and archeological documentation of his effort indicate a respect for the Andrea Doria as something more than just a commercial salvage project.”

Photo courtesy of John Moyer

Ben Roberts, Andrea Doria, present day, Side scan sonar photograph, July 2021; The ship is lying on her starboard side, with her bow to the right and the keel to the top. This survey was done by Ben Roberts of Eastern Search & Survey in collaboration with Moyer Expeditions, LLC.

This exhibition was made possible, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council; the New York State Council on the Arts, with the support of Governor Kathy Hochul and the New York State Legislature; a Humanities New York SHARP Grant with support from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the federal American Rescue Plan Act*; and by a grant from the Lily Auchincloss Foundation.

Curated by Megan Beck, Ciro Galeno, Jr., and Michael McWeeney

Thank you to diver and researcher John Moyer, Salvor in Possession of the Andrea Doria, and survivor, author, and educator Pierette Domenica Simpson.

* Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this exhibition do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.